In the shadow of the second wave of the covid-pandemic and the presidential election campaign of the United States one of the most important frozen conflict of the post-soviet world melted to an open war on the mountainous terrain of Karabakh. The fights beginning on 27th of September between the Armenian and Azeri forces suddenly ended in an unexpected ceasefire on the 10th of November 2020. The agreement tends to completely redraw the map of the region and shift the power balance in favour of the Azeris and their supporters. Meanwhile it means a „little Treaty of Trianon” - as cultural trauma - for one of the belligerents, it offers a revision of a similar former trauma for their opponents. Although it was one of the most important geopolitical change of our days, there are contradictionary reports in the media about the exact effects of the agreement – we try to clear the situation in this blogpost.

The theatre of the autumn war used to be named as „Nagorno (Mountain)-Karabakh” or Republic of Artsakh, although they are not equivalent, and the original „Karabakh” covered a much larger territory in the eastern neighbourhood of todays Armenia between the rivers of Kura and Aras. Nagorno-Karabakh was the mountainous middle part of this region, and in the soviet era, the autonomous territory with the same name covered an even smaller subregion: the central and the south eastern part of the mountainous terrain belonging to Azerbaijan, but with Armenian ethnical majority. This meant that the autonomous region was not directly neighbouring Armenia, a strip with Azeri majority separated it from the Armenia Socialist Republic. The capital of the republic is Stepanakert (Qanqendi in Azeri), with approximately 45.000 inhabitants.

Stepanakert in 2018. Photo: Dániel Segyevy

In the decades following the dissolution of the Soviet Union several military conflicts erupted – mainly based on ethnical disputes (Transnistria, South Ossetia) – most of them developed soon to so called „frozen conflicts”. Tamás Ádány, professor of the International Law Faculty of the Pázmány Péter Catholic University pointed out on an online workshop about Karabakh on the 13th November 2020, that since the middle of the 20th century it is very hard to launch wars, which are ending in an internationally recognized, „lawful” territorial change. It is only possible by the result of self-defence, or by a resolution of the UN Security Council – so it is not a surprise, that those post-soviet territorial changes were not recognised internationally, resulting only de facto independent states.

Border of South-Ossethia and Georgia in 2018. Photo: Dániel Segyevy

Meanwhile the international politics of the last decades is not only influenced by the invulnerability of the borders, but by the right of the nations to self-determination, which helped the ethnical point of view to gain a much bigger role. Besides this - like in the case of many other conflicts – the opponents of the Karabakh conflict tried to prove their territorial claims using the „who was here first” arguments, which are resulting „competing nationalisms”. It is not surprising, that during the 6 weeks war in 2020, the symbolism of different memes, pictures gained overwhelming importance during the informational warfare. The Armenians aimed the mobilization of the international public for their cause. In the first days of the war the efforts were concentrated on the international recognition of the quasi-state „Republic of Artsakh”, later the goal moved to the boycott of Azerbaijan and its main supporter, Turkey, and to emphasize the Armenian role in the international struggle against terrorism (and to emphasize the role of Syrian mercenaries on the Azeri side). Certainly, there were messages, which tried to underscore the Armenian „cultural superiority”. Meanwhile the Azeri side due to their significantly smaller lobby force, not really applied directly to the sympathy of the international public, they tried to mobilize their citizens and military forces – even with patriotic heavy metal.

The parliament in Stepanakert. Photo: Dániel Segyevy

Considering the built heritage, the churches and the cemeteries, it is clear that in the late antiquity and in the early medieval times the region was under the influence of the different Armenian Kingdoms and Principalities, which existed between various empires. Until the early 19th century it changed slightly: Armenian self-governance was impossible on the rim of the Ottoman and the Persian Empires. Meanwhile the Azerbaijani date their direct presence to different khanates existing there since the 15th century (although most of their sources are trying to identify the Caucasian Albania as ethnical forerunner of the modern Azerbaijan.) Our first data about the ethnical composition of the region are originating from the 1830s, the decade following the Russian conquest: then the rural areas of the central and south eastern part of Karabakh had Armenian majority, the urban settlements had both Christian and Muslim inhabitants, meanwhile the sparsely inhabited western and northern region (in the strip between the modern Armenia and Karabakh) lived mostly Muslims, although most of them were nomadians, so the ethnical composition changed constantly. That change has been helped by the considerable population exchange between the Russian Empire and Persia following the Russian conquest: part of the Muslim elite left the region for Persia, meanwhile the majority of the Armenians of Persia moved into the new Russian territories – so the percentage of the Armenians grew in the entire region.

Regarding the ethnical composition of the region for the next 150 years the Azerbaijani and Armenian standpoints differ greatly from each other. They only agree on, that the soviet Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Republic had Armenian majority (with considerable Azerbaijani minority), about the strip between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia they have very different narratives. The at least debated point is, that the region along the river Aras has Azerbaijani majority (however the Armenian sources claim higher percentage for their local minority). This subregion (together with the geographically similar Nakhchivan exclave) is actually the crossriver part of the big ethnical bloc of „Iranian Azerbaijan”, divided by the Armenian inhabited Zangezur Mountains. According to Armenian sources the central and the northern parts of the strip neighbouring Armenia were at least partially inhabited by an Armenian majority, meanwhile the Azerbaijanis claim Kurdish or Azerbaijani majority. The last „peacetime” soviet census in 1979, which is very frequently cited by Azerbaijanis found the population of this region as 95-99% Azerbaijani and there were officially more Kurds (who were counted usually as Azerbaijanis) than Armenians. It has to be added that ethnicity was a political issue in the Soviet Union – the local authorities had big influence on the determination of the ethnicity of individuals – the result of the process was marked in the ID cards of the citizens, so the 99% results of the census could have been very inaccurate in this ethnically diverse region.

The dissolution of Soviet Union and the independence of the Republic of Armenia and Azerbaijan found the region in this state of diverging nationalism – together with the disputed borders it ended in a cruel and bloody war – if somebody is interested how the conflict escalated, more details could be found here. What is more important for us is the result of the conflict: surprisingly the weaker but the Russian backed Armenians gained control over the region: in 1994 they ruled almost the whole Nagorno-Karabakh, the strip to the east and south of it (which effectively connected Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia), and the (ghost)town of Agdam to the east. Following the war which claimed several ten thousands of lives, the Azerbaijani population fled (or have been routed) from the region, and it became a de facto (Armenian) state (Republic of Artsakh) on a considerably bigger territory than the former Nagorno-Karabakh. This „quasi state” is internationally not recognized (not even by Armenia), only three similar, Russian backed „de facto state” supported its statehood. The Republic of Artsakh had approximately 150 thousand inhabitants, and had almost every institution of statehood (parliament, high court, legal system, currency), meanwhile economically and militarily it was dependent to Armenia, symbolized perfectly by the local currency: it has been used merely a souvenir, the local people paid usually in Armenian Dram.

The extradition of the „axe-killer”

Hungary became the closest to the conflict in 2012, during the extradition of Ramil Safarov, the Azerbaijani „axe-killer”. Safarov has been born in Djabrail – the city has been occupied since the 1990s by Armenians, and it was retaken during the recent conflict – and he claimed he witnessed that several of his relatives have been murdered by Armenians. In 2004 he took part in an english language course in Budapest, when he - using an axe - decapitated his fellow Armenian student sleeping in the neighbouring room. He began his prison sentence for the murder in Hungary, but in 2012 Baku initiated his extradition, which was granted by Hungary (in order to serve the remaining years in an Azerbaijani prison). Meanwhile he was immediately released at homecoming and became a national hero. Armenia answered with the breaking of the diplomatic relationships, and the relation between the countries remained cold, although as a tourist a Hungarian could not feel too much about this, and the name of the chess masters Péter Lékó and Judit Polgár is very well known in the chess loving country. To the contrary the official relations are very good with Azerbaijan, the Hungarian government supported them during the recent war and now during the azeri reconstruction efforts in the region.

The Armenian Apostolic Church – one of the oldest in the Christian world – has an independent diocese in the Republic of Artsakh under the leadership of archbishop Pargev Martyrosyan. The Archbishop played an active role during the war in the 1990s, he blessed the soldiers before they went to combat to take Shushi in 1992, and the day after the capture of the city he led a prayer in one of the most important religious sanctuary of the Armenians, the Ghazanchetsots-basilica. That was the first Armenian language prayer since 1920 in the church, which was used earlier as an Azerbaijani ammunition dump, and suffered considerable (partially deliberately inflicted) damage during the autumn conflict.

Pargev Martirosyan, the archbishoph of the Nagorno Karabakh in 2018. Photo: Dániel Segyevy

But why did the Armenians need to control so much bigger territory, than it would be ethnically justified? The explanation lies in the military geography of the region. (If we use a conventional 20th century military point of view.) Although Nagorno-Karabakh itself is a forested „mountain fortress”, which rises with steep slopes above its surroundings to an average height of 1100 m above sea level, for the effective Armenian control a lifeline to Armenia is necessary. The borders of the former autonomous republic are at the scenic city of Lachin to the closest to Armenia. The distance is not greater than 10 kilometres as the crow flies, but there are some „minor problems” with this corridor. First the corridor is a row of serpentines on a very difficult terrain, second – although the road leads directly in the heart of Nagorno-Karabakh (via the old capital Sushi, to the new capital Stepanakert/Qanqendi) – the villages and towns along it had been inhabited by mostly Azerbaijanis – there was heavy fighting for the road.

On this very rugged terrain, the corridor is not very well defendable, in order to use it the defender should control a much broader strip – and this explains the other issues of the defence of Nagorno-Karabakh. The area northward to „the broader strip” is also a mountainous terrain, with a very high, almost inaccessible range at the juncture of the Armenian Highland and the Little Caucasus – it forms a natural defence line to the north – if it is controlled by the Armenians, they can easily defend the northern part of Nagorno-Karabakh (and certainly the corridor as well), if the Azerbaijani forces, they can keep the mentioned area (or at least important parts of it) easily under fire. The strip south to the Lachin-corridor to the river Aras has more gentle relief and it offers a much more adequate battlefield for a conventional (and heavily equipped) army, which can threat the central and southern areas of Nagorno Karabakh – as it was shown in the 2020 war. It explains why it was imperative for the Armenians, to occupy and incorporate those areas into the Republic of Artsakh, and why the loss of these region a tremendous tragedy is. Meanwhile there was a debate – according to the Madrid Principles - in the Armenian politics and in the international politics earlier about those occupied territories, which originally were not parts of Nagorno-Karabakh. There were voices who said, that those territories could be the keys for an agreement, which would officially recognize the Armenian sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh. Before the „velvet revolution” of 2018 the Armenian political life had been dominated by the „Karabakh clan”, and in general it meant considerable political capital in Yerevan, if somebody Karabakh ancestry had. Those political forces did not support any territorial concession. Contrary to this, the present prime minister – who the first leader of the country is, who do not have Karabakh ancestry - had a milder position, and those opposing stands emerged during the recent conflict (and during the protests unfolding) as well.

Meanwhile Nakhchivan, the exclave of Azerbaijan is a „reverse Nagorno-Karabakh” on the other side of the Zangezur Mountains (and Armenia), adjacent to the Turkish border. The exclave had a mixed population earlier, but now the proportion of the Armenians is negligible, and their built heritage is mostly destroyed – the most renown example for the destruction is the cemetery of Julfa.

The war of 2020 raged exactly along the above mentioned geographical conditions and hindrances: the original Azerbaijani attack in the north has been stopped following a short retreat, but the second attack from the south gained rapidly ground, and it finally reached the central and southern regions of Nagorno-Karabakh: the Azerbaijani forces managed to occupy the emblematic and culturally important city of Shushi, cutting the highway to the Lachin corridor as well. It has to admit, that the mass use of drones, and another 21st century military methods, changed lot on the warfare and made less use of the geographical advantage of the Armenian positions, the Azerbaijani army could attack the remote mountain stands more effectively than it was anticipated.

Meanwhile the Azerbaijani Army first did not disclose figures of their casualties, both sides lost about 2800 soldiers.

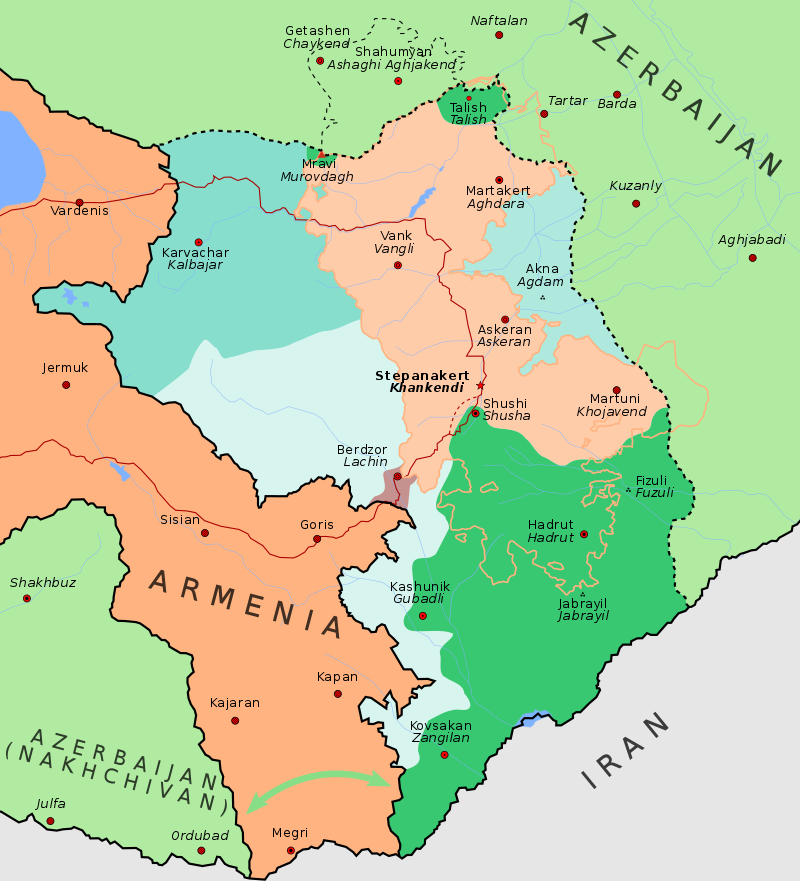

The armistice signed quite unexpectedly on the 10th of November 2020 did not make the situation clear enough in the following days. According to the first news, the Azerbaijanis could control the newly occupied areas, independently whether they were originally part of the Autonomous Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh (which officially the integrant part of Azerbaijan is) or not. Other sources claimed, that the Azerbaijani forces will gain control on the whole area between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, and the newly occupied part of Karabakh north to Stepanakert. As an exaggeration of this version there were claims in the media, that only Stepanakert and its suburbs, and the Lachin corridor will remain under Armenian control. The reason, why such a contradictionary reports could spread is, that a different Azerbaijani and Armenian regional classification coexisted in the area, and it was not quite clear, which areas the original Russian text of the agreement really covers.

The truth is, that the agreement contains both territorial changes: the Azeri forces will control all of the recently occupied territories (which are de jure parts of Azerbaijan), also the southern areas of Nagorno-Karabakh, the city of Sushi along the corridor highway AND the Armenian forces should leave every territories still under their control, which was not part of the original Nagorno-Karabakh. The northwestern Kalbajar district should be evacuated until the 15th of November, the eastern Agdam district until the 20th of November, the Lachin district until the 1st of December. Meanwhile – contrary to the first news – the northern part of Nagorno-Karabakh will remain under Armenian control (with the exception of a small strip retaken by the Azeri) – together with the narrow Lachin corridor 2000 Russian peacekeeper will safeguard the region.

The map of the region after the ceasefire on 10th November 2020. (source)

It has been reported previously, that there will be an another „corridor” leading from Azerbaijan to the Nakhchivan exclave – but in the latest news it seems to „transform” into a mere transit right – it means that Armenia has to allow the transit passage of Azeri passengers and goods on his own territory to Nakhchivan. (The Armenians can control the traffic, but without firm reason they cannot stop it – like the GDR in the case of the West-Berlin transit after 1971.) This itself is a giant improvement for the almost isolated exclave – until now the „mainland Azerbaijan” could keep the contact with the exclave via Iran.

On the 15th of November the handover of the Kalbadjar District began, not without dramatic events. The inhabitants of a little village, Charektar set their houses aflame instead giving those to the Azeri. One of the most important Armenian built heritage, the Monastery of Dadivank built between the 9-13th Centuries lies also in Kalbadjar District, the local armenians said farewell hand-in-hand to the building – according to the latest news the Russian peacekeepers will secure the Monastery, and make possible for Armenians to visit it. (Like the Italian soldiers in the case of Monastery of Decani in Kosovo.)

Simultaneously the Russian forces also arrived, and built 25 control points: 18 on the remaining territory of the Republic of Artsakh, and 7 further in the Corridor of Lachin. Some sources mention, that with this move the situation in the corridor have been more or less stabilized: the exodus of the local Armenians slowed down, although some of the Yerevan protests have been organized by the inhabitants of the corridor: according to the agreement.

Until now at least 50 thousand Armenians fled from the areas recaptured or regained by the Azerbaijanis and from the Corridor of Lachin. Meanwhile the Azeri and the Russians began to plan in the earnest, how to clear the scars of war away, and to normalize the life on the affected areas. The Russians would participate in the repair and rebuilding the damaged or destroyed Armenian residential buildings, as well in the renovation and protection of the Armenian cultural heritage. They would secure the safe passage of 2-3 convoys daily from Lachin to Stepanakert via the Azeri occupied Shushi, until a bypass road is not completed (if ever completed). Meanwhile the Azeri have big plans regarding this most neuralgic location: Shushi. They would make the city to the „cultural capital” of Azerbaijan, there are going to take place festivals following the reconstruction, and a new hotel named „Victory in Karabakh” would be built in the city – some sort of provocation could be easily discovered in those ambitions, which makes a bit questionable the success of this Azeri rebuilding and repopulation policy.

The Dadivank Monastery. Photo: Dániel Segyevy

Altogether the peace agreement is a tremendous victory for Azerbaijan, and a catastrophe for Armenia ant especially for the Republic of Artsakh. According to the treaty the territory of the quasi-state will shrink from 11.450 km2 to approximately 4.000 km2, and it will be militarily totally vulnerable and dependent to the Russian and Azerbaijani forces. Bálint Kovács, the head of the Department of Armenology of the Pázmány Péter Catholic University thought on a workshop about the Nagorno-Karabakh-situation that the quasi-state institutions of the Republic of Artsakh will remain in place, the question is that how many of its Armenian inhabitants will flee in the future to Armenia. He claimed that Russia might be the real victor of the conflict: meanwhile he is directly involved in the other frozen conflicts (Transnistria, South-Ossetia) of the broader region, here could play the role of a judge acclaimed by both parties, and his soldiers expanded their sphere of influence hundreds of kilometres to the southeast from their Armenian bases, without a single shot. According to some analysis the Turkish support aimed to help gaining ground for the Russians, and so the weakening the western influence in the region.

The new situation and the rather sketchy nature of the agreement awakens many thoughts and questions:

- What will be the fate of the Armenian population on the areas regained by Azerbaijan? After the first days it is more or less clear, that they will leave most of those regions.

- Will Azerbaijan respect the territorial integrity of the remaining Republic of Artsakh? The victory gives a tremendous legitimation for the rather autocratic leader of the country, therefore most probably he would not change the present situation, but it could change in the future, if the Azerbaijani leadership needs further political legitimation.

- How will the defeat affect the rather democratic Armenia and Artsakh? Could they politically allow to keep themselves to the agreement, or will the pressure be to big in order to escalate the conflict? What other can they offer now for a more stable, internationally more recognized agreement than the hopeless (but bloody) military resistance?

- How will the growing influence of Russia on the (rather democratic) political institutions of the two mentioned Armenian states?

- How will the fact effect the geopolitical situation of the region, that Azerbaijan gained a corridor to its main ally, Turkey. What will bring the political closing of Turkey and Russia (and according to some sources Iran)?

- Who will finance and build the new Stepanakert-Lachin road bypassing Shushi? When will it be completed on the very difficult terrain? Until the completion will the land connection to Stepanakert really work?

Central European (Carpathian Basin) parallels ((dis)similarities)

In the Hungarian common talk (on rhetorical level) we can found parallels between the situation in the Little Caucasus and Székely Land and Transylvania in various sources. Meanwhile the Ambassador of Azerbaijan in Hungary said in 2017, that „Part of Azerbaijan has been simply ripped apart by Armenians. I am living in your country for a while, I know your history. What the Hungarians experienced with Transylvania, we experienced in the case of Karabakh”, Nagorno- Karabakh is often depicted in the Hungarian media as the „Armenian Székely Land”.

Although the loss of Transylvania and Székely Land runs in the Hungarian remembrance quite parallel, it is quite obvious that any parallel with the Karabakh situation leads to contradictionary commitments. The too simplified attitudes do not help us to understand, what is happening in Karabakh, but – very cautiously we can track the similarities: the words of the ambassador referring to the loss of Transylvania in 1918-20 reflect of the Hungarian point of view between the two world wars, which aimed the total revision of the borders, meanwhile the Székely Land parallel represents the Armenian point of view on the ethnically based borders of Nagorno Karabakh.

László Jakab - Dániel Segyevy

The original version of this article was publsihed in Hungarian in December 2020 on the Telex.hu.